Center for Automotive Research recently presented their draft findings on what connected and autonomous vehicles mean for our communities, as part of the November Stakeholder Summit for Prosperity Region 9 (the “Greater Ann Arbor Region”). The research team’s work has largely been guided by the discussion at the League’s September Convention on Mackinac, where we used a breakout session to hear from members about the concerns they had in thinking about how to adapt to self-driving cars. A final report is expected in January, and will be the topic of a session at our 2017 Capitol Conference.

“Nobody wants to be Betamax”

Of course, many of these findings will still be hypotheticals-what CAVs could mean-since we’re still very early in the development and adoption curve. As the CAR team noted, truly automated driving is still not available on the market, even in limited and access-controlled conditions like freeway driving, let alone in wide enough use to understand people’s reactions to it.

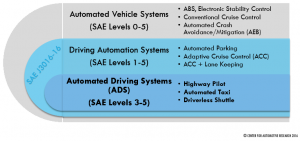

Current CAV technology is at “level 2”, supporting human driving. Actual automated driving is anticipated in the next 5 years, but is not on-road yet.

The most ambitious promises from companies like Tesla suggest options may arrive in the next few years, but widespread use is likely years beyond that: CAR’s Eric Dennis noted that automotive technology typically takes up to 30 years to reach 90% saturation of the on-road fleet of vehicles. And, as one participant noted during discussion, “nobody wants to be the Betamax,” the road agency who invests heavily in the wrong direction by guessing too early what needs to be done.

For example, in September the question came up, will US DOT or MDOT be offering funding to pay for all the new striping needed on streets for automated driving to work? CAR’s Dennis noted that striping is “beneficial, but not necessary” for current approaches to automated vehicles, and that AASHTO and SAE are working on guidelines for CAV-oriented lane markings-cities and other road agencies should probably not rush out to preemptively stripe every local street in advance of such guidance.

But nor should we be passive observers

A wait-and-see approach to developing technology has its limits, though. Letting driverless tech alone choose the pace and direction of change, and make demands on our communities, will not yield the best results. Instead, we should be thinking ahead about how to incorporate the opportunities this tech could offer: planning, not reacting.

Is this the entrance to a great downtown, or a grand prix starting line?

We’ve been down the road of letting mobility tech call the shots before, by letting cars drive development patterns for the past half-century. We’ve built bypasses around our towns in the name of traffic flow, and watched our Main Streets dry up for lack of customers when everybody drove around town instead. We’ve turned neighborhood streets into pairs of one-way multi-lane drag strips, making it potentially fatal to walk across the street to visit your neighbor. We continue to tear down historic buildings in the name of having “enough” free parking, punching holes in our communities. Sure, all of this means that we can get places 30 seconds faster, but only by making huge steps backwards away from creating great places.

Planning for CAVs, rather than letting them plan for us

As our cars become self-driving, we should make sure that this change works for our communities, rather than making our communities work for autonomous driving technology-we need to plan intentionally to utilize these new technologies for our benefit, rather than simply wait and see what changes the technology wants us to acquiesce to.

Dr. Lisa Schweitzer captures this in Choice and Speculation an article in the latest issue of Cityscape:

“According to most speculation, driverless technologies will “transform” things. Technology is always the actor, like some unalterable force that sets the terms by which cities and human life will unfold. [However,] Individuals, governments, and businesses have choices about how they create, sell, and use technology; We have choices about how we distribute the benefits and burdens wrought by driverless vehicle technology. Those social, economic, and political choices can influence human life in cities just as much as, if not more than, the technology changes, and those choices will shape the technology as much as the technology will inform and influence choice.”

On this note, the work we’ve been doing with CAR and PSC helps to capture our local policymakers-concerns about driverless tech, and to compile what’s known about the state and trajectory of that tech, and we look forward to presenting those findings.

Building on this foundation, though, we’ve got plenty of work left to do in figuring out those social, economic, and political choices ahead of us. This technology will offer monumental changes in how people might live our lives, and we have to recognize the limits of policy in societal change–but that limit is not 0.

I’ll be writing more on this in future posts, but welcome your thoughts in the meantime on how we accomplish this, whether in person, via email at [email protected] or on Twitter @murphmonkey.