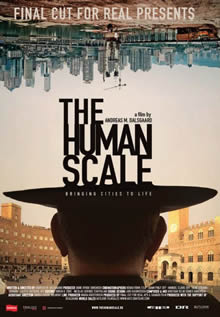

This year’s festival slogan is “One Great Movie Can Change You.” Among the many great films at the festival that could do just that: “The Human Scale,” Danish filmmaker Andreas M. Dalsgaard’s documentary about revolutionary architect Jan Gehl’s vision for redesigning cities for people instead of cars.

The film opens with this sobering fact: 50% of the world’s population lives in urban areas. By 2050 this will increase to 80%. So how will we accommodate those 6.5 billion people in cities that are already struggling to meet people’s most basic needs?

“We have to get the cities to change their ways. If you pay attention to the smaller scale, inviting people to walk and bike, you get a more lively and livable city, a safer city, a more sustainable city,” says Gehl, who has spent the last 40 years observing and recording how people actually use public spaces, in order to build the empirical evidence necessary to change the modern approach to urban planning. For most of the 20th century we’ve been counting cars not people, Gehl says, and the result has been an urban landscape that’s designed for traffic flow at the expense of human habitation.

“The Human Scale” proves its point by taking viewers on a profoundly dramatic tour around the globe, from troubled cities that serve as disturbing cautionary tales to urban meccas that offer hopeful glimmers of what can be achieved with vision and political will.

It begins in Copenhagen, where a former desert of urban modernist thinking has been transformed under Gehl’s influence into one of the world’s most livable, bikeable cities.

In Melbourne, Australia, city leaders literally reversed a decades-long trend of urban flight by closing some roads to traffic and giving them back to pedestrians and cyclists, creating true city squares, and converting unused alleys into public spaces. Almost like magic, the changes are bringing the city back to vibrant life and a flood of new residents are returning to the revitalized urban core.

In China and Bangladesh, Dalsgaard shows how the desperate drive to “catch up” with the west is repeating the mistakes of auto-centric planning to disastrous effect, destroying culture and community even as it fuels economic growth.

In Christchurch, New Zealand, we see how the earthquake that destroyed the city’s center also created an extraordinary opportunity for change—but now the short-term thinking of the national government and moneyed developers threaten to subvert the people’s will for change. It’s a story that echoes powerfully here, where cities like Detroit now have a similar opportunity to build something new and sustainable amid the ruins of the old and failed.

Building for cars creates a physical structure that separates and alienates people from each other and from their environment—from suburban islands and mega high-rise apartments that residents rarely leave, to freeways that wipe out neighborhoods and trunk-line highways that divide downtowns. Building more and bigger roads to accommodate more traffic only creates more traffic, Dalsgaard says. Building public spaces and walkways for people increases human interaction, promotes health and enhances public safety.

I thought about our own drive into Traverse City, which boasts one of the most beautiful and vibrant downtowns in Michigan. But to reach it, you have to drive in through the township on a five-lane highway choked with high-speed traffic and lined with high-rise resorts blocking the view of the water.

As we approached, we saw a young family of four stranded in the center turn lane. Mom was carrying the baby while Dad was pulling the toddler in a wagon, their heads scanning back and forth, helplessly waiting for a break in traffic that was never going to come. All they wanted to do was to walk less than 100 feet from the putt-putt course on the south side to their hotel on the north. We slowed to a stop, waving them to cross while our car blocked the traffic. At first they just stared at us with a mix of doubt and disbelief. Then they scurried across, waving gratefully when they reached the safety of the other side.

One hundred feet. An impossible blockade. Most families wouldn’t even try.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

During the Q&A with the filmmaker at the screening’s end, an audience member asked where we could find political leaders who could implement human-centered design into our urban planning, to build these places where people truly want to live.

His answer was that the federal and even state government is too enmeshed in politics to facilitate this kind of ground-level change. It’s the leaders of the cities themselves who are in the best position to change our cities, he said.

Hopefully this film will indeed change the people who see it. And if enough of us are changed, we can help change the future of our cities, and the world.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]