(This piece originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 2020 issue of The Review magazine.)

Created by the federal Tax Cut and Jobs Act at the end of 2017, Opportunity Zones have all the features of a gold rush: things are moving very quickly, everybody is excited, and nobody actually knows if there really is gold in them there hills.

The best-case scenario that Opportunity Zones have promised is a mechanism to bring investment into neglected low-income neighborhoods, supporting local services and business development. Because the incentive has no approval step, oversight, or even transparency for local or state governments, though, there’s high potential for abuse: it could end up being yet another way that predatory capital investors extract value from communities already suffering from deindustrialization, racial discrimination, or both. Somewhere in between is the possibility that OZs have no significant impact, that there’s very little fire under all this smoke.

The challenge facing communities is how to steer Opportunity Fund investors towards projects with true local benefit and put guardrails in place to prevent the worst—all without being able to see what, if anything, is happening with the incentive.

First, where are these zones?

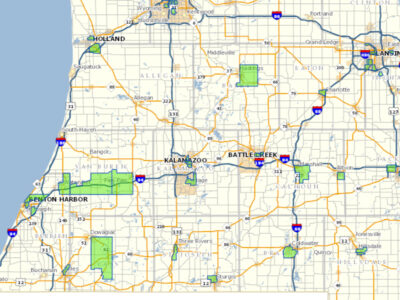

The Snyder administration had to designate a certain number of census tracts as OZs within the first three months after federal establishing legislation was passed, with very little information about the incentive or opportunity for on-the-ground input. A map of Michigan’s zones is at https://miopportunityzones.com/ and there is currently no way to add, delete, or edit zones from that map.

This means some municipalities and neighborhoods could see OZ investment (and have no way to opt out), and others never will. Many of the strategies emerging for communities to benefit from OZs do have application in other places—just without the incentive’s boost to investor return.

OZs were designated in both urban and rural areas around the state; check https://miopportunityzones.com/ for specific locations.

If you’ve got a zone—what does that mean?

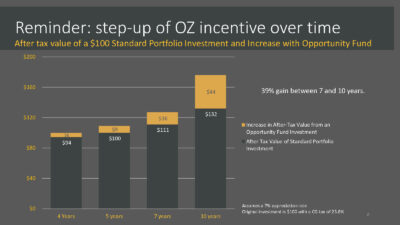

Opportunity Zones are a federal tax shelter that allows investors to avoid taxes on capital gains by investing those profits in business or real estate development in designated low- and moderate-income communities for multiple years. The greatest benefit for investors comes after 7 to 10 years of investment, and the incentive was only authorized through the end of 2026, creating pressure for investors to move quickly and secure long-term investments. As a federal tax incentive, the only reporting required is between the Opportunity Fund investor and the IRS—local government and states do not have any formal role in the process, and may never even know which projects the incentive is being used for.

While most OZ investment activity so far appears to be in real estate development, the incentive targets capital investors, not developers directly. This is a point of difference from financing that targets particular development priorities, like MEDC’s Community Revitalization Program (CRP) or MSHDA’s Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) allocations.

The newness of the incentive (and the suddenness with which it was created), the shotclock for investments, and the very large amount of capital that could theoretically be invested have created a lot of buzz and attention. There are several challenges this poses for municipalities, though each challenge can be addressed.

OZs incentivize holding investments for longer-terms over rapid flipping. Longer-term investing can help host communities, but also has led to a surge of up-front interest in this time-limited incentive. (Image from Governance Project, at 2019 Convention)

Who is going to be investing?

The OZ incentive does not apply to all investment, only to investments of capital gains within a short period of time after these gains are realized. An investor in an Opportunity Fund has to not just have a large enough capital gain to make the marginal tax benefit significant, but must be able to afford tying up those funds for as much as a decade. Most OZ investment is therefore expected to come from large-scale investors such as private equity funds, institutional pension or endowment funds, or extremely high net worth individuals—investors who tend to be looking into a community from the outside, to have little connection or familiarity with the local context, and to be concerned only with financial return.

Some local investors will have capital gains to use, however, and the OZ incentive could bring impact investing within reach for these investors. By moving a Main Street investment from negative return to merely below-market return, a combination of OZs and the emotional appeal of investing where they live may get some locals to bring some money home from distant and anonymous investments. Providing local attorneys and accountants, or the local community foundation, information on the OZ incentive and potential local investments is one way to reach these stakeholders.

Make the best projects easiest

While municipalities have no direct role in approving Opportunity Fund investments, they can use the tools they have available for directing any investment: local incentive policies, zoning ordinances, and capital improvements plans should provide clear and easy paths for developers and investors to do the projects the community wants to happen. A combination of guardrails against harmful projects and incentives or promises of quick approval for beneficial ones can do a lot to steer investment.

This applies whether the project is financed through an Opportunity Fund or not—developers prefer easy projects over hard projects, so communities can use their tools to make the good projects easy. (At our September Convention session on OZs, Jill Ferrari from development firm Renovare put it bluntly: “If you’re not in the Redevelopment Ready program, we’re not even going to look at a project in your community.”)

…and make them easy to find

Another emerging best practice for Opportunity Zones is that communities should proactively market the projects they want to happen. This has multiple purposes. Any municipality engaged in the Redevelopment Ready program will recognize the first: putting your community on the map for investors who probably aren’t going to find their way to you on their own. The second is to keep those investors’ attention on the projects that will provide the most benefit to the host neighborhood, rather than waiting to react to potentially detrimental projects. Finally, holding the local conversations necessary to identify, prioritize, and communicate those beneficial investment opportunities may trigger the interest of local investors who had previously overlooked opportunities right in their backyard.

One model for this marketing is the OZ Investment Prospectus popularized by Accelerator for America. These documents combine community-wide economic and quality of life data, usually sourced from county or regional economic development organizations; walkthroughs of the district- or neighborhood-scale character and goals for each local Opportunity Zone; and descriptions of individual property or business investment opportunities within those zones.

In short, Opportunity Zones could be a beneficial catalyst to designated neighborhoods, but could also be an example of what Jane Jacobs called “cataclysmic money,” a large outside force that acts despite communities’ interests rather than for them. The best defense may be a good offense in this case: getting out in front of the investors and leading them to the projects that will actually add to our distressed neighborhoods and municipalities.