We’ve talked a lot about how our local communities are squeezed by Michigan’s failed municipal finance system: that our primary revenue stream, property taxes, is designed to fall behind; that the state has plundered our second largest funding source, revenue sharing, to the tune of $8.6 billion and counting to patch its own budget; and how the dominance of public safety costs and statutorily required duties absorbs nearly all remaining budget.

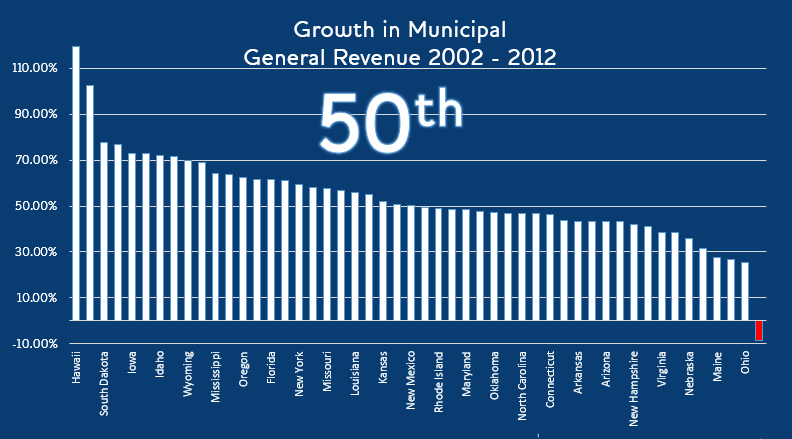

Between our constitutional revenue limits and the state’s underfunding of revenue sharing, Michigan local government budgets are in last place nationally.

But as we work with communities around the state on securing development that meets local goals, we are finding that the state’s broken municipal finance scheme additionally inhibits local efforts at self-help: nearly all of the tools communities have available for economic development assume adequate funding, especially from property tax. Like Lucy holding a football for Charlie Brown, the state has enabled a broad array of local development tools that many local governments can’t use effectively.

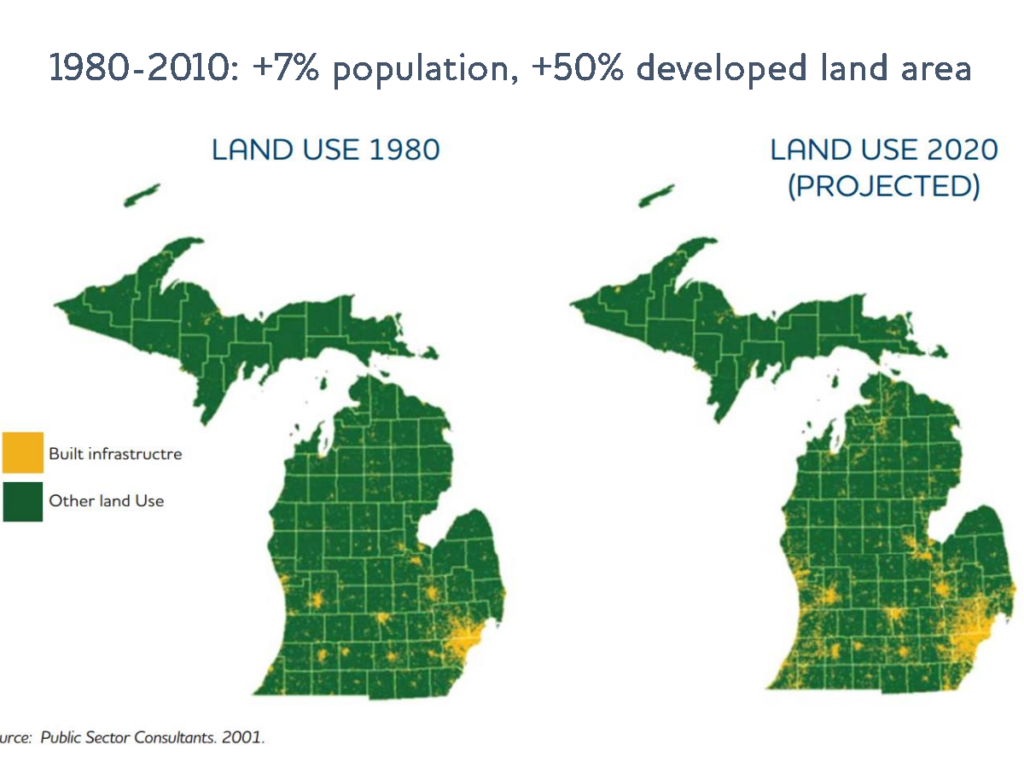

Due to the state’s constitutional limits on property tax revenues, the only way municipalities can even keep up with inflation over the long run is by “additions” of taxable value–that is, new construction. Traditionally, this has supercharged what Strong Towns has termed the “growth Ponzi scheme,” a pressure for constant new development to pay for the maintenance of past development: with Headlee and Proposal A causing our tax revenues to fall off even more quickly than they would otherwise, the perverse incentive of building ever outwards to maintain local budgets has contributed to our expansion of infrastructure and urbanized area across the state even while population has been flat–we have so much difficulty fixing the d*mn roads (and sewer mains, water lines, etc.) because we have so many more of them per capita than we did 40 years ago.

While our population growth has been sluggish over past decades, we’ve spread out rapidly, taking on massive infrastructure maintenance costs (also known as “potholes”) in the process.

The League has attempted to refocus attention and investment on existing places through our placemaking initiatives, and in our work with the state’s Redevelopment Ready Communities program: to reinforce and support existing community investments instead of the build-and-abandon cycle. But city and village attempts to take this path are constantly bumping up against basic math. Outside of a handful of hot markets, infill development in Michigan requires the local government consider incentives to bridge the gap between construction costs and local market conditions.

Public incentives for private development can support important community goals such as remediation of toxic contamination, affordable housing, living wage jobs, or preservation of historic landmarks. But our broken municipal finance system often closes off the additional benefit of ongoing tax revenues. (Incentives can also be used badly, of course, and I always encourage doing the math!)

Nearly every community economic development tool allowed to our cities and villages prevents a construction project from fully contributing to the local budget: they reduce property tax payments, as in PILOT agreements for affordable housing; they divert revenue for particular purposes, such as brownfield TIF for site remediation; or they waive new tax revenue for a period of time, such as abatements for obsolete property renovation.

And, thanks to our broken system, by the time the property is fully contributing property taxes at the end of the abatement period, its value is likely to have been artificially depressed by Prop A and Headlee, slicing off long-run benefits that development might otherwise bring. (Obviously the value of a property can change over the course of a decade regardless and fiscal forecasts should plan accordingly–our system just puts a heavy thumb on the negative side of the scales.)

For municipalities to truly leverage our array of property tax-based development tools, they have to be large enough or wealthy enough that they can absorb any incremental service demands while not collecting tax revenues–meaning they’re not necessarily the communities with the greatest need for effective tools to support development. (The 20-some cities with local income taxes are a special case, as most of the property tax-based programs allow the municipality to collect revenue from new residents or employees via this income tax to contribute towards costs of services.)

Relying on property tax incentives for local development support is extremely limiting in a Headlee-constrained world.

Sometimes the idea of “spin-off benefits” or “multipliers” arises as a way that tax-abated development can indirectly support local budgets–this is less likely than it intuitively seems. If a new development makes surrounding homes more appealing, driving up home values, Prop A caps the taxable value of each home, and as sales trigger “pop-ups” of individual home values, Headlee rollbacks prevent the local government from seeing any new revenue. Similarly, nearby businesses might see more foot traffic, but since that business activity is not subject to local taxation, the municipality again sees no budget benefit from that activity. Until the point where resident demand is driving new housing construction or major renovation, or where business growth leads to physical expansion–“additions” under Headlee”–tax revenue does not increase.

Economic development activity may have very visible effects in the community–without contributing to the municipal budget.

Again, the economics of development mean that public support is often needed, especially to secure public goals like environmental cleanup or affordable housing: increasing local tax revenues is not the only metric to be used in evaluating incentive programs. Ideally, though, the local toolkit would be large enough to also allow communities to use incentives in ways that better support their budgetary ability to provide basic services.

(This post is adapted from a pair of presentations Murph gave recently on municipal finance for planners and economic developers, intended to help those practitioners understand the math that their city managers and elected officials are grappling with.)