Last month Kalamazoo’s City Commission cut down their lot size requirements in several residential areas. Notably, these amendments weren’t done in the name of permitting anything “new” in those neighborhoods—but to support and reinforce what’s already there and remove some headaches from residents.

These lot size amendments, one piece of the city’s “neighborhood zoning repair” work, are a great example of incremental code reform, and one that’s worth a look for any community with older residential areas, where overly restrictive zoning ordinances add burden to maintaining the traditional neighborhood fabric.

I had the chance to help Kalamazoo with this effort, through the League’s work in support of MEDC’s Redevelopment Ready Communities program: for the zoning and GIS enthusiasts in the audience, I’ve included some short methodology notes to help get you started with your own analysis.

These tree-lined streets of front porches and sidewalks are an important part of our cities’ neighborhoods. Too bad so many of them have been made illegal through zoning.

The annoyance tax of mismatched residential zoning

Many of our favorite traditional neighborhoods predate the widespread use of zoning: Michigan’s first city and village zoning enabling act was in 1921, and the township zoning enabling act didn’t come until 1943. During the home construction boom that followed World War II, communities adopted zoning ordinances that reflected the current practices of the time—applying them broadly and bluntly not just to new subdivisions, but also to the neighborhoods that already existed, where they were—not a great fit.

A 1950s ranch home with a private driveway from the street needs a 50- or 60-foot-wide lot, where a 1920s two-story home with alley access or a shared drive can fit comfortably on a 40- or 45-foot-wide lot, for example. But apply that new 60-foot expectation to the older neighborhood as a legal minimum, and suddenly you’ve rendered wide swaths of homes non-conforming. While an “existing non-conforming” lot, structure, or use can be continued in perpetuity, the ongoing mismatch creates friction for the residents of that older neighborhood.

Non-conforming status can make it harder or more expensive to get a mortgage, or home insurance, or a home improvement loan—because the bank or insurer wants to know the lot will still be usable if the house burns down. Even where the local ordinance provides an escape clause (e.g. that any existing lot under residential zoning can be used for a single-unit house), buying or refinancing that historic house can require extra documentation of that fact. Setbacks or lot coverage requirements might still make rebuilding challenging, as well as limit opportunities for additions, decks, garages, or other improvements. My friend David, a Realtor, refers to systemic hurdles like these as “annoyance taxes” that accumulate and subtly discourage people from living in these neighborhoods or from investing too much money or energy into their homes.

Where zoning renders the typical parcel “too small” for a home, houses destroyed by neglect, fire, or other catastrophe are hard to replace, leaving gaps in the neighborhood.

Kalamazoo’s neighborhood zoning repair

As part of Kalamazoo’s neighborhood-by-neighborhood planning efforts, the city’s planning staff has been looking for “zoning repair” needs—where the zoning doesn’t match the existing neighborhood context, and the existing neighborhood is valued as it is. When the League performed a “zoning stress test” for the city (as part of Kalamazoo’s Redevelopment Ready Communities technical assistance support from MEDC), I took a deep dive the zoning ordinance’s lot standards for the Edison Neighborhood, where local staff had identified repeated friction between the requirements and the existing neighborhood fabric. They then extended this approach to other neighborhoods which shared this challenge to finalize their recommendations to the City Commission.

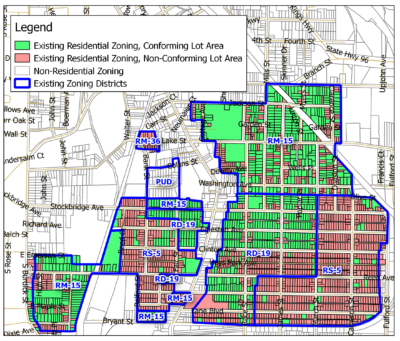

First, I looked at lot sizes, finding that two-thirds of the residential parcels in the neighborhood were “too small” under the existing zoning. In parts of the neighborhood, every home on every block sat on a non-conforming lot, because of the lot sizes used in the initial plat. In other areas, century-old lot splits created more scattered non-conforming parcels. (Using GIS, I selected all parcels within a given district, then did a “select by attribute” on those parcels to identify lots with areas below their zoning district’s minimum, and set a non-conforming flag for those; then repeated this for each other district.)

Before the update of lot size requirements, two-thirds of residential parcels in Edison were below the minimum lot area for their zoning district.

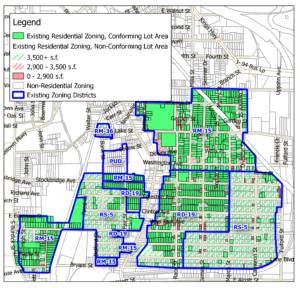

The next step was to test a few new lot size thresholds to see what would bring the zoning into compliance with neighborhood patterns, and suggest some revised minimums that would fix most problems, leaving only a few outliers that might need separate solutions. (This repeated the above process using a few different test lot areas and flagging each parcel for the lot size threshold that would make that parcel conforming. For simplicity, I used thresholds that were already in use within the zoning ordinance, either as some other district’s minimum or as a per-unit minimum in districts that allowed duplexes.)

Green-striped and red-striped parcels would be made conforming by lowering lot size requirements by different degrees.

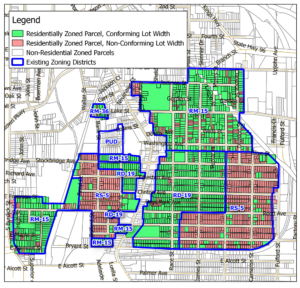

Moving on from lot area, I next looked at lot width: again, over half the homes in the neighborhood sat on parcels that were “too narrow” under the existing zoning, having been platted for smaller lots. (If you have a parcel layer that includes a frontage or width attribute—possibly from assessing data—you can filter on this; without this, or in the case of irregularly shaped lots, you may need to approximate by drawing bounding boxes around your parcels and then filtering on the widths of those.)

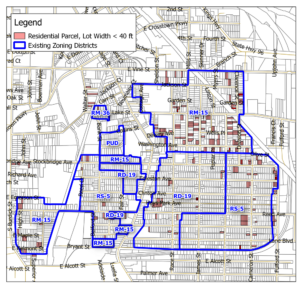

The 60-foot minimum lot width of the R-5 district made nearly every Edison parcel in that district non-conforming.

A 40-foot minimum lot width fits the neighborhood’s original pattern much better. (Apologies for color scheme change; few enough reds left they were hard to see!)

As applied, in Kalamazoo and in your community

Kalamazoo’s staff repeated my analysis for a few other neighborhoods to calibrate the thresholds, as shown in their presentation to the Planning Commission. The City Commission adopted a package of lot size and coverage amendments at the end of January. While significant, as the staff memo notes, these are not the last word on these neighborhoods, but a temporary patch: “These amendments are intended to relieve the pressure of the large quantity of nonconforming lots that exist throughout while City staff work to thoroughly update all the residential zoning districts in the first half 2019.”

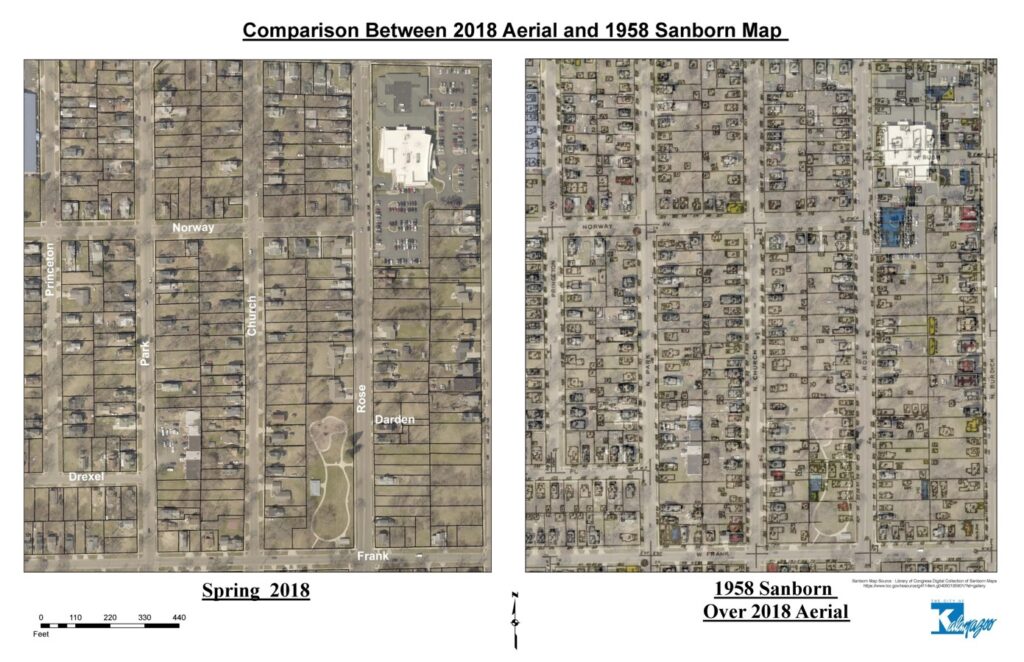

Kalamazoo staff created this amazing overlay of a 1958 Sanborn fire insurance map on a current aerial photo of part of the Northside neighborhood, showing how much of the historic neighborhood pattern had been lost over time.

In some neighborhoods, this ongoing work might mean additional tweaks; in others, more significant changes to the zoning might be needed to bring it in line with the neighborhood’s vision and plans. In general, these lot size amendments won’t bring any dramatic changes to Kalamazoo’s neighborhoods—where they enable new homes to be built on vacant lots, they will be reinforcing the built patterns already in the neighborhood. What they will do is peel away one layer of annoyance tax from residents already living there, an important piece of enabling people to love where they live.

Kalamazoo isn’t alone in facing this challenge—Muskegon also recently reduced the lot size requirements in some neighborhoods to better fit the existing neighborhood patterns. Not coincidentally, fixing out-of-scale lot requirements is the #1 recommendation for neighborhood form in the User’s Guide to Code Reform that we produced with CNU and MEDC. Both Kalamazoo and Muskegon provided input to that project about their code hurdles, and I used an early draft of the Guide to target my work with Kalamazoo.

While the GIS analysis certainly provides attractive maps, there are certainly ways to take on this zoning repair activity without it. For example, in smaller areas, comparing the minimum lot size in the zoning ordinance to the original plat map for a traditional neighborhood is an easy step. The plat will include lot widths and depths that can be used to quickly compare a “typical” parcel’s size to the zoning ordinance’s minimums. Alternately, just looking for any place your zoning ordinance applies a 60-foot minimum lot width or 6,000 square foot minimum lot area to a neighborhood built pre-World War II is a good indicator that you have an issue.