Economic growth what-if scenarios are (again) a hot topic in the wake of Amazon’s location announcements, so I’ll throw my own—non-Amazon related—offering on the table.

For all the time Michigan has spent talking about things like “talent attraction” and “economic growth”, we’re not especially prepared to deal with success on that front. How do we handle the scenario where we actually get the growth we’ve been working towards?

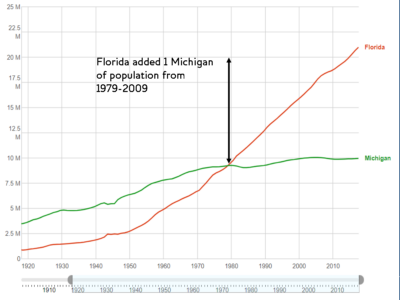

Consider: since 1979, Michigan’s population has been essentially flat. Over almost 40 years, we’ve added only half a million residents—not that large a number in a state of almost ten million, the 8th largest at the start of that period. By contrast, some states are picking up that many residents every four or five years. In fact, Florida and Michigan were about the same size in 1979, but Florida grew by 1 Michigan of population in the following 30-year period.

Florida passed Michigan’s population around 1979, adding about a million people every 5 years since then.

Assume some combination of our talent attraction efforts with the push effects of hurricanes, flooding, and Zika super-mosquitos cause Michigan and Florida to exchange fortunes, and our population starts growing by 100,000 every year, instead of every decade. Where would Michigan’s new arrivals go?

Our bigger, core cities?

The easy, popular take, which I myself have offered in the past, is, “there’s plenty of room in Detroit!” (Or Flint, Saginaw, Battle Creek, Lansing…) The challenge with this prescription is that there are also a lot of people already in those communities who aren’t feeling the benefits of our current models of economic development and growth: a flood of newcomers (or returnees) coming in from out of state will cause rampant gentrification, harming existing residents, if we don’t get better at development without displacement before relying on our larger legacy cities to absorb that growth.

Our suburban periphery?

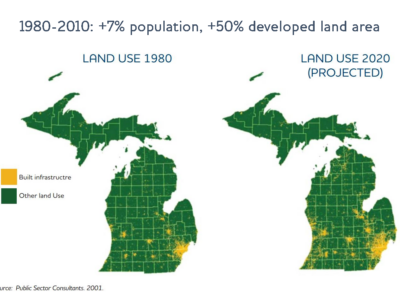

Michigan’s classic strategy over the past decades has been to expand outwards—whether we’re growing on net or not. The state has expanded its developed land area by 50% in 30 years, a better (er, worse) than 5:1 ratio of infrastructure expansion to population growth. As we’ve found out, adding infrastructure so much faster than we’ve added new people to pay for it means that each of us has to pay more. This “strategy” has required higher gas taxes and vehicle registration fees, higher utility bills, and higher property tax bills, just to slow the pace of entropy.

While our population growth has been sluggish over past decades, we’ve spread out rapidly, taking on massive infrastructure maintenance costs (also known as “potholes”) in the process.

Even if financial sustainability weren’t enough reason to halt our unproductive expansion, planning to continue putting our growth on our edges would degrade both the natural amenities so important to Michigan’s identity and the agricultural land that will be that much more important as drought threatens the irrigated farms of southwestern states—as well as missing a chance to reinvest in existing communities.

Our small towns?

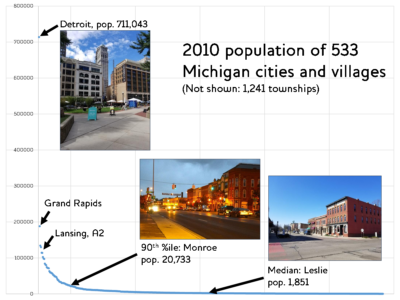

Looking beyond the bigger metro downtowns and suburbs, the League has over 500 members, and most of those are small. Very small: the median League member has a population just over 1,800, and the average population is around 10,000. A great many of these smaller communities have lost population over time, and could probably benefit from having some new neighbors. But with some of these communities struggling with lost employers, others with tourist economies making housing scarce, and many suffering an aging housing stock that’s too cheap to get a mortgage and rehab loan for, simply moving a bunch of new people in isn’t a straightforward answer here either.

Half of Michigan’s municipalities have fewer than 1,851 residents.

It’s not hypothetical

This isn’t just a thought exercise: there are some significant “pushes” that could bend Michigan’s population curve upwards. Consider the damage wrought by record hurricanes hitting the east and gulf coasts in the past few years, the apparent permanent state of fire in the west, and the long emergency of water shortages in the southwest, and the relative appeal those places have enjoyed starts to fade a bit.

In addition to the national baseline growth rate of a few million people every year, a disaster response expert recently pointed out to me that the US had seen 1,300 disasters since Katrina, that 1 Million homes are destroyed by disaster every year, and that many of those people relocate rather than rebuilding. Every week, there are people abruptly looking for a welcoming community to call home.

As we look out into the next few decades of climate change fueling the fires, floods, and hurricanes, this will only accelerate. As Popular Science noted last year, “Looks like we’re all moving to Michigan!” by 2100AD—but they advise people beat the rush, and “go nail a quality spot while the pickings are still slightly more plentiful.”

The White House’s new climate report echoes this in dryer tones, noting that the northern portion of Michigan “will be among the few places where the value of warmer winters outweighs the cost of hotter summers” for prospective residents, suggesting that this could “revers[e] long-standing trends in out-migration from the Midwest” and that changes in national migration patterns will contribute to population growth in the region.

The report agrees that we’re not quite ready for this to happen: “More research is needed to understand how cities in the Midwest might be affected by long-term migration to the region.”

The work to be done

Michigan is an entire generation removed from conditions of real population growth, and our elected leaders and professional staff generally lack experience operating in that condition. Unless we want to exacerbate the deficits of our overbuilt edge infrastructure, the loss of farmland and scenic resources, and the vast disparities of wealth and opportunity within and between cities, we’ll need to rebuild or adapt a number of tools to handle growth well:

-

Our Project for Code Reform collaboration with CNU, MEDC, and MAP seeks to bring good development codes within reach of small communities.

Planning and building great places: the technical skills are probably the least difficult step and we’re already underway on some of these: the League and our partners around the state have been working on basic tools of placemaking, Redevelopment Readiness, and zoning code reform for the past few years.

- Financing equitable development: a bigger lift is figuring out the mix of private, community, and public capital needed for healthy and equitable placemaking. We need some combination of reinvigorated affordable housing programs; cooperative ownership, investment crowdfunding, and other community investment models; rehab loan loss reserves for weak housing market areas; PACE, net metering, and similar energy finance programs. All of these exist in some form, but are tiny fractions of the public and real estate finance domains.

- Narrative and consensus-building: the hardest piece in any community is likely to be figuring out which directions to work in. Many of our industrial communities saw an economic peak decades ago—some lumber and mining towns a century ago—and have been dealing with decline for much or all of their memory. A number of our suburban municipalities have existed almost exclusively in the flat portion of Michigan’s population curve. Many places talk about themselves as “built out” and having no place left to add new residents or businesses.

A growing Michigan would mean each of hundreds of places across the state will need to have new and unfamiliar conversations about their local opportunities and cautions, adopting a particular local blend of tools to support that scenario. It’s a challenging hill to scale—and of course relies on the state both supporting local efforts, rather than preempting any creative program, as well as fixing the structural problems with our municipal finance system.

Ultimately, though, this is work that will lead to a much more positive growth scenario than “winning” Amazon.