I’ve had a firehose-drinking few weeks of thinking about how connected and automated driving could affect our communities. “Could” remains the operative word, at least for self-driving cars, since the buzz still outweighs the reality by a significant factor.

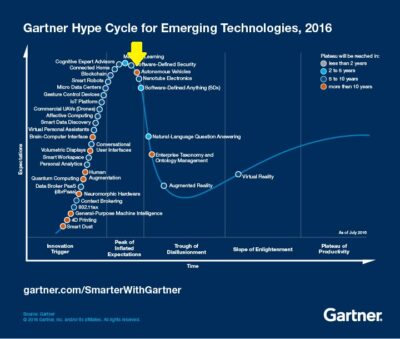

“Gartner’s Hype Cycle” for 2016 shows autonomous vehicles (yellow arrow) just about at the top of the “peak of inflated expectations.”

Capital Conference 2017

At the League’s Capital Conference, Harry Lightsey from General Motors shared time-lapse video of one of GM’s vehicles navigating the streets of San Francisco, apparently in autonomous mode. (Caution: If you get motion sick easily, maybe skip the video.) Nicole DuPuis from National League of Cities followed with thoughts from NLC’s Future of the City work.

We followed with a breakout to talk about the hot-off-the-presses report from PSC and CAR to Prosperity Region 9, outlining near-term issues that our communities need to grapple with. These range from figuring out what training police officers need to handle a potential traffic stop or crash involving an automated vehicle, to completely rethinking parking (how much, where, and at what price?), to understanding the role of public transit agencies in ensuring equitable access as the technology changes.

Briefing with MSU’s new CANVAS research center

The following week, I was invited to speak at a Great Lakes International Trade and Transport Hub briefing at MSU. Several faculty in MSU’s engineering college presented on their CANVAS–Connected and Autonomous Networked Vehicles for Active Safety–research center. Other presentations ranged from Andreas Mai’s V@S model estimating $5 Trillion in global value from CAV over the next decade, to the Stratford, Ontario, city-wide connected mobility pilot projects.

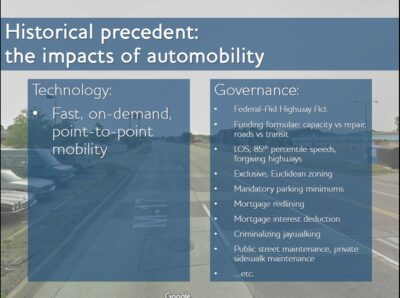

My own comments included a summary of the Region 9 findings. More importantly, though, I focused on the role of policy in shaping the impacts of automated driving-just as policy decisions, from engineering standards to real estate finance programs, played a huge role in determining what personal automobiles meant for our communities.

Technology has a significant impact on the shape of our communities–but the policy context that technology operates in can matter even more.

Future Cities regional workshops

Yesterday, I attended the first of a series of regional meetings that Center for Automotive Research is running on behalf of MDOT and MEDC, examining the impacts of connected vehicles, automated driving, and “mobility services” such as ZipCar, Uber/Lyft, and bikeshare.

CAR are the automotive experts, and cautioned that “level 5” general-purpose automated driving is still far enough over the horizon that they can’t make any reasonable predictions about when it will arrive, let along become widespread. Mobility services, however, are widespread in larger cities now, and both connected vehicle and driver-assist technology (such as lane-keeping and blind-spot detection) is becoming more common on new vehicles, so these may be more critical to plan for now.

One “fun” fact from the CAR presentation were estimates that full deployment of connected vehicle tech could save up to 22% of fuel usage even before hybrid or electric tech or increased CAFE standards are considered. Considering how heavily our transportation funding is based in the gas tax, this could pose a Big Problem by eroding maintenance budgets that much more quickly.

New readings look downstream

Two good pieces came out last week as well, on different facets of CAVs:

- CityObservatory dives into CAVs, traffic, and road funding. “Given that we think that many of the persistent problems with our current transportation system stem from getting the prices wrong, we think that the way that autonomous vehicles will change the cost and price of urban transportation will be key to shaping their impacts.” They suggest that a VMT model with “surge pricing” that considers where and when the vehicle is driving could be the best way to fund our transportation system and manage congestion as ridesharing and automated driving become more popular.

- Benedict Evans, a tech venture capitalist, thinks down some rabbit holes about the effects of both automated driving and auto electrification: e.g. if electric vehicles become widespread (or AVs can fuel themselves without you), your neighborhood may no longer need gas stations-and the convenience stores attached to those gas stations may go away too, without a captive user base of people buying gas. And, “well over half of US tobacco sales happens at gas stations, and there are meaningful indications that removing distribution reduces consumption,” meaning reduced car crashes might not be the only health benefit of electric and autonomous vehicles.

What’s next? Watch carefully, plan flexibly.

Where the Capital Conference and MSU events surveyed some potential effects over the next 1-10 years, the CityObservatory and Evans pieces demonstrate just how far-reaching the impacts could be over the longer term.

I’d be a sucker to say I knew what these outcomes will be, though, despite (or because of?) all of the above. My expectation is that we’ll start seeing semi-automated trucking platoons on our interstates and ridehailing/taxi-style or micro-transit automated services in larger urban areas in the 5-10 year timeframe, and we’ll need to remain agile in figuring out what combination of directing, managing, and adapting to the impacts of these changes is possible.

As envisioned in this Swedish video, CAVs and placemaking can be very compatible, if we prioritize space for people over space for vehicles.

Meanwhile, carshare (like ZipCar or GM’s new Maven), ridehailing (like Uber or Lyft), and bikeshare are options available now that can support local placemaking efforts to expand transportation choices available to residents-and can help shape the travel habits that we bring to automated driving.