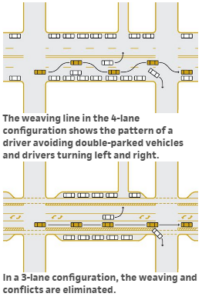

This graphic from NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide shows how road diets can improve safety and traffic flow.

Many a traditional main street has suffered from bloated roads: where a street was once lined with bustling sidewalks and businesses, the pavement was expanded more and more in the name of moving traffic, at the expense of parking, sidewalks, and eventually the health of the businesses themselves. Through traffic doesn’t spend dollars while it’s speeding by, after all.

Enter the road diet. A silly name, perhaps, but it’s an enormously important concept for community wellbeing.

A road diet takes a wide road and skinnies it down-or, at least, skinnies down the amount of space devoted to moving vehicles by quickly. The goal is a more balanced street: one that provides not just for the orderly movement of through traffic, but also supports access by people on the sidewalk, people on bikes, people getting on a bus, people parking their cars and going into a store, people unloading delivery trucks. In short, a street that works for, rather than against, the area around it.

How big is too big?

The best candidates for a road diet are one-way streets with three (or more!) travel lanes, or two-way streets with two travel lanes in each direction. If you have these types of streets in a traditional business district or neighborhood, they were almost definitely widened at some point, and probably widened more than they need to be for current traffic needs.

Take a look at the traffic counts on these streets. As a quick rule of thumb, each through traffic lane can carry about 10,000 cars per day-or a little less, if there are a lot of driveways, on-street parking, or similar things that slow traffic. A 4-lane two-way road with less than 20,000 cars daily can probably be 3 lanes (one each way and one left turn) with no loss of capacity and fewer severe crashes. A 3-lane one-way with under 20,000 cars daily can probably work well as a 2-lane one-way.

Also look at how wide the lanes are. Many of these roads were built with 12- or even 13-foot wide travel lanes, but experience shows that these wide lanes actually lead to more severe crashes than narrower lanes-people drive more cautiously when the lines are closer together. As a result, a 10.5-foot wide lane (11 if there’s significant bus or truck traffic) can be safer while still carrying traffic effectively.

The Kalamazoo PlacePlan led to a road diet on Portage Street, improving access to Washington Square.

What do you do with the leftover pavement?

After you examine the number of lanes and the width of those lanes, chances are you’ll have space left over between the curbs.

With 8 feet of leftover width, you can add either on-street parking on one side or a bike lane on the other. With 12 feet (such as on a 3-lane one-way to 2-lane conversion) you can put parking on one side and a bike lane on the other.

In either case, you’ve just provided better access for more people, ideally without any costs for concrete or asphalt-just paint and signs. As an added benefit, moving traffic is now separated from the sidewalk a little bit, providing a safer and more inviting place for people to walk, which means more customers walking into businesses or more attractive homes.

A 2012 MDOT research project showed that 4-to-3 lane road diets could reduce crashes by as much as 40%, and provided additional recommendations for planning and implementing such projects.

Ypsilanti’s West Cross Street before the road diet–a 3-lane race track slicing through the neighborhood.

Better streets support investment

Improving access, safety, and comfort on a street supports a healthy business environment. For an example, take a look at West Cross Street in Ypsilanti. West Cross has been the front door to Eastern Michigan University for over 150 years, and has long had a small, convenience-oriented business district.

West Cross is also M-17, though, and in the 1970s was made into a one-way street with 3 lanes in one direction. By the 1990s, the business district was struggling, with high business vacancy and turnover, and many of the buildings in disrepair. Remaining business owners pointed to the high-speed traffic and lack of parking as a major challenge.

A parking lane, improved crosswalks, and better organized sidewalk support foot traffic to businesses.

In the early 2000s, the city worked with MDOT to implement a road diet as the key piece of a neighborhood plan. Since the street only had about 15,000 vehicles per day, it could be changed from 3 through traffic lanes to 2 (still one-way), creating enough space for both on-street parking on the left and a bike lane on the right. This only required restriping the street and adding signs and parking meters, but worked well enough that the city implemented step two in 2011, utilizing TAP funding to add intersection bumpouts, stamped concrete crosswalks, and street trees.

These changes have supported significant reinvestment in the business district over the last decade, with some support through facade matching grants by the Ypsilanti DDA and Washtenaw Eastern Leaders Group. At least 10 new businesses have opened in just a few blocks, and several existing businesses have expanded or made significant facade improvements.

The most significant rehab created four new business spaces across from EMU, with lofts above and an extended sidewalk bumpout for outdoor cafe seating. Developer Andrew O’Neal notes he would have thought twice about the project if the road diet hadn’t created on-street parking–and looks forward to eventual two-way traffic.

While there’s plenty of work left to do-the street remains a high-speed, one-way strip that can make it difficult for visitors to find specific businesses-both the streetscape improvements and improved business conditions have made West Cross a much better front door to EMU and amenity for neighborhood residents.

A number of smaller building and facade rehabs have helped make the corridor more attractive overall.

Richard Murphy is a program coordinator for the League. You may contact him by email at at [email protected] or on Twitter @murphmonkey.