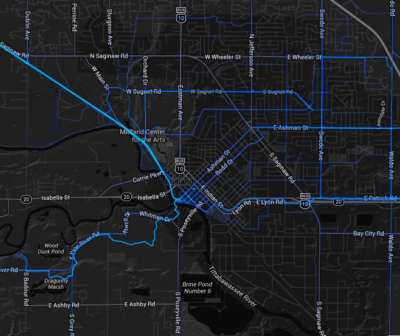

Strava’s heat map of bike/walk activity in Midland shows the popularity of that city’s recreational trails–but surprisingly little bike/walk access to the major employment center.

Fitness tracking app Strava recently began offering its data-millions of walking, jogging, and cycling trips around the world-to cities and transportation agencies. For a price, of course: this is a revenue stream for the app developers-so what’s in it for the public agencies? As Gizmodo explains, bike/walk traffic data is traditionally much harder for agencies to collect than traffic data, but, with apps like this, “we’re all walking sensors now:”

Strava’s first customer, Oregon’s Department of Transportation, paid $20,000 for data from nearly 20,000 cyclists in hopes that it might help them figure out how to handle the steadily increasing bike traffic in cities like Portland. “Right now, there’s no data. We don’t know where people ride bikes,” Jennifer Dill, a professor and urban planner at Portland State University, told The Wall Street Journal. “Just knowing where the cyclists are is a start.”

This type of data can support placemaking efforts, especially as we look to support walkability and offer residents a range of transportation options: knowing where people choose to walk, jog, and bike-and where they don’t-helps us diagnose our community’s streets and target improvements.

Know your data’s limits-and leverage them

This can’t be done without some caution, though. As many commenters on the Gizmodo piece point out, the Strava dataset includes two biases that we need to consider in our planning.

The first issue is a self-selection bias: since the data is collected by smartphone users using the app, it only measures the habits of people whose income, age, and comfort with technology lead them to seek out and use smartphone apps to track their travel. Also, as the app is targeted at “fitness” users, it will likely be skewed to those trips, and include a smaller sample of people who are walking or biking to work, school, shopping districts, or other destinations. Even those app users who are tracking their bicycling commute are likely to be biking by choice-rather than being forced to because they lack access to an automobile. The app data will be less useful in identifying the travel patterns and needs of low-income residents and others who walk and bike out of necessity.

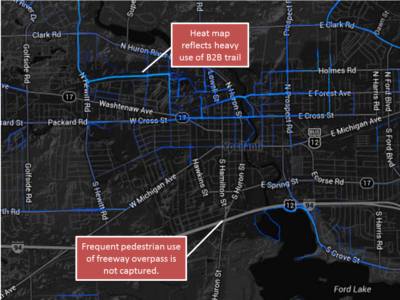

The second concern is a confirmation bias: because of that skew in who the users are and why they are traveling, they are more likely to have the luxury of choosing routes that already work well for biking and walking. This data will point to heavy activity on the scenic rail trails and state park trail loops, while overlooking the people who brave dangerous freeway interchanges on foot to get to work, or the road that could deliver recreational cyclists into downtown, if only it had a bike lane.

Strava’s walking heat map shows the already high-quality rail trail near EMU’s campus, while completely overlooking the more hostile, but still heavily used, Huron Street / I-94 interchange.

Because of these, planners should therefore be double-checking the Strava data against conditions on the ground. While the data might point to highly-traveled routes that need some improvements, in many cases, the outcome should actually be to improve the biking and walking experience on routes that Strava users are NOT recording.

If on-site observations or neighborhood engagement show that certain streets are critical walking and biking routes for day-to-day essential travel, but the travelers using fitness apps are avoiding those routes, then planners should be asking why: what’s wrong with those routes that causes travelers with choices to avoid the, and how can they be made better for those travelers with no choice? Not only will this use of the data serve a broader segment of additional residents, it will also help extend the attraction of a community’s downtown districts and other major nodes by bridging current barriers.

Share and share alike: supporting virtuous cycles

In many cases, privately developed apps rely on the availability of public data to function, either directly or implicitly. Transit app Ototo, for example, wants to tell transit planners what people are searching for, so they know where people want to go, but it can only serve metro areas where the transit agencies have published open data sets. By providing ready access to public datasets, local communities (and state agencies) can support the private development of apps, which can then feed data back to the communities on how people are using the apps-and, by extension, how people are interacting with the places around them.

Several efforts try to help public bodies shorten this cycle even further: organizations like Code For America, or events like the National Day of Civic Hacking (coming up May 31-June 1!) bring motivated software developers together to design, prototype, and build new applications for public data. In order to have the greatest benefit for communities, though, these efforts need access to both data and the public sector staffers who know the subject matter.

As mobile apps continue to grow in popularity and capabilities, cities should continue to look for ways to leverage the data generated-and to support the process with data of their own. Even though the field of mobile apps is only a few years old, cities and states that have engaged effectively are already benefiting.