“Staying Home, Staying Safe” Reinforces the Importance of Having a Home

By: Richard Murphy,

July 30, 2020

A lot of us have been spending a lot more time at home lately, either laid-off, furloughed, working-from-home, or caring for family. This has drawn acute attention to the way that community wealth hits closest to home for people: whether they have an appropriate, affordable, accessible place to live. The lack of that place harms not just the individuals facing housing instability, but cascades outwards to impact the people next door, the surrounding neighborhood, and the local schools.

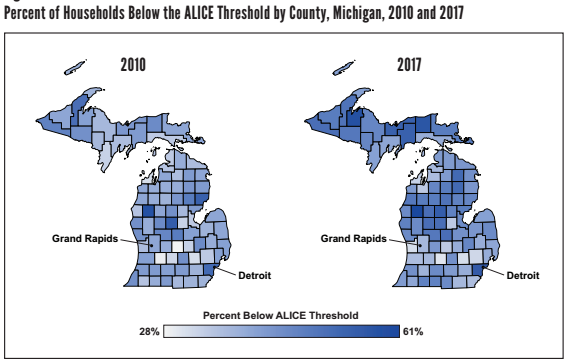

The United Way’s ALICE score–“asset-limited, income-constrained, employed”–shows that over a quarter of households in every Michigan county has trouble affording basic needs, and that the problem is growing

The coronavirus pandemic has so far caused a critical, but hopefully temporary, crunch on local budgets. But if it causes a lot of people to lose their homes through foreclosure or eviction, we could see a repeat of the long-term local budget damage that the subprime crash caused. As we all experienced in 2008, widespread housing instability can send municipal taxable values into free fall, harming public service funding for decades.

To be clear, having a place to live is first and foremost a vital public health need, and always has been. The pandemic has just led more of us to be thinking about it, and about the ways housing instability ripples outwards. As our friends at Center for Community Progress ask, the coronavirus has created an all-hands-on-deck moment for us: “Can we see the challenge of recovering after the pandemic as an opportunity to rebuild not the same, but better than we were?”

In Traverse City’s Depot Neighborhood, Habitat for Humanity has created “net zero” homes that bring residents’ energy costs to almost nothing, supporting residents’ stability while reducing climate impact.

Recognizing the vital public health need of staying home, and the challenges posed by widespread unemployment, Governor Whitmer, the Michigan Supreme Court, and various federal programs took action to limit certain evictions and foreclosures. How well our residents and our communities ultimately recover from the pandemic, though, requires that we look beyond these time-limited emergency measures and begin putting in place longer-term systems for ensuring people have adequate housing.

- A recent study by the Michigan Poverty Law Program and University of Michigan Poverty Solutions found that 200,000 evictions are filed in Michigan every year—one for every six renter households—with negative impacts on the health, safety, and well being of those residents even where evictions do not result. The report provides county-by-county data and policies that municipalities can work with their local district courts on, or advocate for at the state level, to reduce these harms. (Check out our Aug. 5 webinar with one of the report authors and MSHDA staff for more information.)

- “Housing first” approaches to homelessness emphasize that a safe, permanent, stable place to live is fundamental and should not be conditioned on other behaviors (such as sobriety or psychiatric treatment). These have demonstrated benefits in terms of improving health outcomes, reducing the chance of potentially fatal encounters with law enforcement, and significant long-term savings to public budgets.

- Taking a close look at code requirements for new homes, and removing unnecessary barriers to development, can help fill neighborhood gaps for modestly-priced housing without direct subsidies. Our work with CNU and other partners in the Project for Code Reform offers some direction for getting started in this direction.

- Vacant public land can be used to support community land trusts, co-operatives, or other social housing models that offer both stability and short-term affordability to current residents as well as building a stock of long-term affordable homes for the community. (Cities should ensure that these tools are diversifying the homes available within neighborhoods, and not just concentrating affordable housing within low-income places.)

Using a mix of strategies to prevent displacement and create a diversity of housing choices within neighborhoods and across communities is a critical piece of community wealth building—both to support residents’ health, safety, and welfare, and also give the community as a whole the flexibility to adapt to changing conditions.